The storm, it scares me.

One of my earliest memories is that of the 1997 El Nino.

It is a vivid memory, as if that moment 22 years ago is playing right in front of me at an IMAX theater. It haunts me often, and I find myself jumping out of bed in the middle of the night at the mere thought of it.

My mother does not like the memory either, since she is the only one who was old enough to fully grasp it. It is reminder of what could have been, and it is an alternate future she, and I, are happy did not materialize . That is why, I think, she would rather forget it. All she tells me is that it must have been sometime in November of 1997.

The storm waters, they came charging, like a herd of wilder-beast. Litter by litter, they pounded the mud walls of our small hut, threatening to knock it down. They shouted at us, warning us to seek refuge elsewhere. My mother clutched to my screaming toddler of a younger brother, and prayed. I, shaking, held her tightly, and waited.

The drought, it scares me.

One of the most vivid memories I have is that of the 2011 East African famine.

It is a vivid memory that gives me sleepless nights whenever I think of it. Every time I think of it, a chill goes down my spine. I feel anger rising up my esophagus, wanting to spill unprintable words at those responsible for it. But then, something tells me to keep calm, and wait. ‘Maybe…’, the thing tells me, ‘…This is just a bad memory and it shall one day go away’.

Despite waiting, this bad memory has never rally gone away. It was a Thursday afternoon, and me and my then classmates were just window shopping at a mall in the Nairobi CBD. A few minutes into the exercise, a newsstand pulled me in, and I yielded. On the top rack of the meter high rack, stood a daily whose headline screamed: ‘Kenya Worst Famine in 60 years’.

Its cover page contained a skeleton of a Turkanan woman. A famished baby was suckling away at her leathery, left breast. The right one, long depleted of its milk reserves, lay down-flaccid. The baby’s eyes were yellow, as were hers. Cracked lips, I saw a fly hovering over her bony head-sensing death.

The brown waters, they scare me.

I do not have to think into the far past to remember the destruction that brown, storm waters can bring. I remember them from just the past year. I even narrated them in the story of Mutio’s farm. The brown waters, they were violent, and destroyed everything in their path. They flattened houses, and destroyed farms such as Mutio’s.

March and April are normally some of the driest months in Kenya. Last year was an exception though. El Nino-like levels of rains were experienced all over the country. I was an working as an agronomist at that time, and all the farmers I worked with in Eastern Kenya suffered losses. The Athi River overflowed, washing away farms.

I briefly traveled to Central Kenya, and it was the same case. In Nyandarua County, where the Sabaki river flows, it was flooded. Many farms were destroyed. I traveled to Western Kenya for my father’s funeral, and it was no different. The Kuja-Migori river was flooded, and its brown waters destroyed farms wherever they passed by.

Brown soils, they scare me.

In fact ,they are thing that scare me most. The image of that Turkanan starving woman has never left my mind, and I hoped, those eight years ago, to never see such an occurrence again. But those are just wishes. I saw a couple in 2016, and earlier this month the stories started coming back: Another famine was in the offing.

I waited, and sure enough, it came. I saw the pictures of Kenyans in Baringo and Turkana, starving. The brown soils of their environment spoke of their bare, harsh reality. And this is only regarded as a famine because the affected people have gone for days without food. Under ‘normal’ conditions, one meal a day would do.

Then, slowly but surely, the images started trickling in. The men and women were just as shriveled as I last saw them on that daily. The children, the least said the better. It is painful seeing those pictures. They spread like wildfire on Twitter, and a hashtag was quickly started to raise funds for their aid.

All was well until someone made an observation I share too:

Kenyans do not have to make donations to save their fellow citizens from drought. We do not need food aid. This was a noble cause, and a necessary one given the prevailing circumstances. Lives are at stake, and politics aside, those are people who will die if interventions do not come in time. Some have died already. It is a sad situation. But it is not the first time. Neither will it be the last one, unless.

Unless, something changes.

In January 1997, the Kenyan government declared a state of national emergency due to droughts that were threatening the lives of millions. By the end of the year, those El Nino rains that I described at the very beginning started pounding our farms. No plans were made to tap into that vast water resource and utilize it in boosting production.

There’s a Kiswahili proverb that goes something like, ‘Majuto ni mjukuu’. It translates to ‘Regret is a grandchild’, and simply means that our inaction will birth a problem in the future, however distant. And that’s exactly what government inaction did. In 2000, the country faced its worst drought in almost 4 decades.

Five years later, another one hit us. Just as people were running around campaigning for the 2005 Referendum, millions were starving in Northern Kenya. Those doing the campaigns spoke of nothing on how they will prevent such situations in future, and in 2011 the mother of all droughts gave birth to the long-expected grandchild.

Last year Kenya received generous amounts of downpour, as I have described earlier. All rivers around the country were brown, muddied by the soil they picked upstream. They zigzagged the nation. Destroyed farms in some areas, encouraged growth in others. What was constant, however, was that no adequate, sustainable measures were put in place to conserve such water for future use.

Despite such heavy downpour, no adequate measures had been put in place to tap into that vast amount of water. The Athi-Sabaki-Galana river is the second longest in the country, yet not a single dam lies along its stretch. All the waters that made it grow 10 times its size in the last year went straight into the Indian Ocean.

Now, here we are again.

The rains have failed, and people are starving. No, let me rephrase that. The government has failed, and people are starving. The situation in Turkana and elsewhere is simply a matter of poor planning by both national and county governments. Effective usage of water resources, like L. Turkana, is just one aspect of it.

There are issues of food distribution systems, seeing that some areas experienced bumper harvests of the staple maize. There are issues on genuine political goodwill, as some sociopaths use it as a political tool. Until these issues are properly addressed, then we will continue to have these problems coming back to haunt us year in year out.

We will continue having, on one side, vast amounts of brown waters, and on the other one hectares and hectares of browner soils. Bare. Dying. Such is life in a country whose government does not effectively plan for its people. In such a situation, changes need to happen.

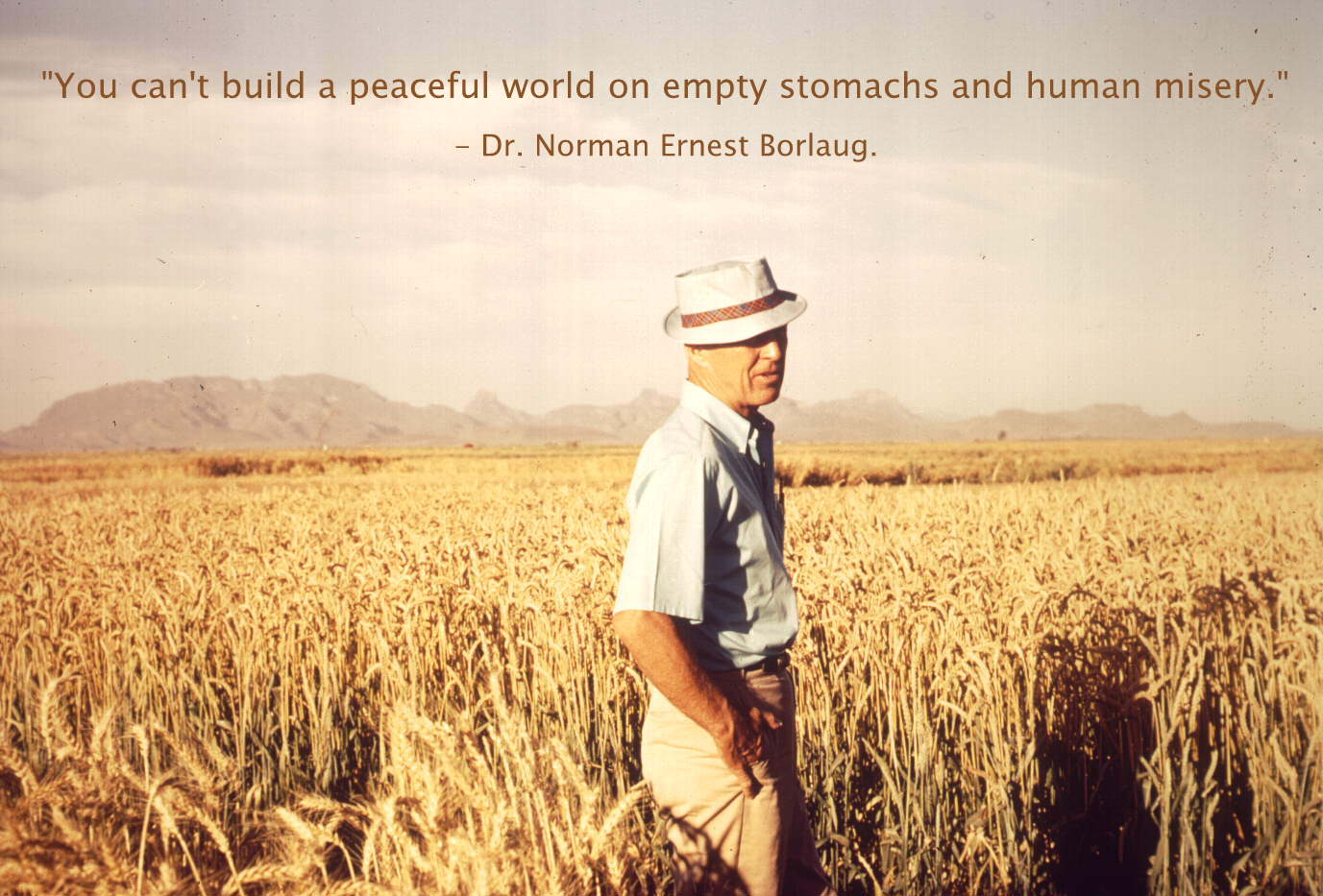

As Norman Borlaug once put it, “The first essential tool for social justice is adequate food for all people”. All those people starving deserve justice from the government that, at least on paper, swore to protect them. That includes protection from hunger, I believe. Until that happens, then changes must be made.

If that does not happen, I fear, one day it will give birth to very bitter, and violent grandchildren…

I don’t know what those changes are, maybe you do. What do you think?