Sambo and Zole had been standing in front of Nairobi River for sometime now. It was just a few minutes past 7 PM, the darkness having swallowed the sky. Lucky for them, there were those high mast streetlights Kenyans call ‘Mulika Mwizi’ to aid with visibility.

Zole often found that name quite strange, as if the whole intent of having street lights was to illuminate potential thieves, to get them out of their hideouts. Such a bleak way to view life, she thought.

Both of the rickshaw pullers had left by now. Only the man distilling the river’s water to brew the popular Chang’aa drink was left behind. The light from his fire supplemented that from the streetlight, revealing what the two rickshaw pullers had left behind:

On one part of bank, the thick, stinking paste of stool indicated that one of them was involved in the rudimentary exhauster business. They provide an essential service, and extract sewage from the few toilets around the slum, and dump it into the river.

Next in line was the pile of rotting and rotten produce. Most of it was fruits: Bananas, mangoes and avocados. There were also some vegetables, most;y kale and spinach. Houseflies were hovering all around them.

The river’s waters, full of plastic from upstream, struck the paste of stool violently, and started washing it downstream. The pile of organic produce met the same fate, and fruits started flowing along the river.

The waters went, to somewhere where Zole knew they’d be used to grow those thick-leafed vegetables sold in the local markets. Those same greens that are brought to the markets every morning.

The same vegetables that will feed the nation.

The thought of it nauseated her.

She knew, that all she was seeing in front of her was a consequence of zero value addition. And not just the agricultural value addition Sambo had mentioned. She remembered the exact words he had, earlier that evening, used as the vegetable cart pusher moved past them:

“You challenged me on what I’d focus on if I were The Great Farmer King. And so I told you the first three. The fourth agenda, put simply, is value addition. I would support an ecosystem that encourages agribusinesses to tap more into this vital area.

As Death, our long lost friend, told us while observing the river of mangoes and avocados, agriculture is a principal component of a majority of African economies. Agro-processing is one of the industries poised to offer job opportunities to the bulging youthful population and meet demands for processed food.

The continent heavily relies on aid and is a net importer of food despite having the most arable land and hence a viable multi-billion dollar processing industry. Despite potential challenges such as water and energy consumption, it is still one of the most viable solutions to the poverty and employment facing not only Kenya but also other African countries.”

But that was not enough as far as she was concerned. That was Sambo’s dream, if he were the Great Farmer King. And they were noble ideas, she believed in them, and their potential to generate tangible change.

But she also had her ideas, if she were The Great Farmer Queen.

To her, value addition went far beyond just passing produce on conveyor belts, creating pulps or formulating flour. These, she believed, had already been talked about, and there was no need of repeating them.

To her, value addition was something a bit more intimate, something whose lack had created the murk of a river that was flowing in front of them. She often wondered, would deifying the river, as the Indians had done with the Ganges and Yamuna, bring more attention to the need for its reclamation and value addition?

Would it precipitate the required sense or urgency?

The foetus kicked.

“What’s the matter?” Sambo finally broke the silence, while, lightly, rubbing her upper back.

“Walk with me, it’s getting cold. Mother will be worried”.

And so they started their journey back toward her home. The alleys had now grown darker, and they grasped their way for a few minutes before Sambo remembered that his phone had a torch. He took it out of his right trouser pocket and lit the way as Zole spoke on:

“You see Sambo, whenever I step here and see what is happening to Nairobi river, I tend to think that it is the people who need more value addition before we can even think of the agricultural products.

Say, what would lead one to dump raw sewage into a river? What would make another one grow food using those same same waters,while being fully aware of its consequences? Don’t you think, my dear husband, that there is something missing?”

Sambo nodded his head, as they approached a pool of muddied water in front of them. The house was now just a few meters away. She had grown in this area, and easily knew which step stone was real and which one might be a sponge placed by naughty boys.

She laughed, thinking of the day Abdul, her elder brother, plunged into one such pool. The laughter was almost immediately replaced by a somber expression, remembering their childhood prankster of a friend, Mageto.

He would have been 28 today. That was, had his body not been discovered at the City Mortuary 2 years ago. With 7 bullets pumped into his body at close range. The police said he was a hardened criminal, but no one ever came forth to prove it. His sweet 18-month daughter will never know her father.

Well, as the saying goes, “Mazishi kwa wote”.

Such is life, they said, for those with no value worth adding to.

She quickly discarded this thought and spoke on:

“If I were The Great Farmer Queen, Sambo, I would first focus on adding value to the people. Anything else, including adding value to agricultural products, is secondary. You know Sambo, you gotta create a society that gives people the opportunity to achieve their potential.

Without this, your idea of feeding the nation is in vain. It will, at some point, collapse right under your nose. You see, if, say, you, my dear Great Farmer King, provided good sanitation services, no one would have to dump their shit into the rivers.

This, especially, the Athi is the same river whose water you intend to grow crops that you will value add, isn’t it?” Sambo nodded in agreement, ashamed that he had overlooked such an important thing.

By now they were just ascending the last hill and onto a wider space. All along, he had been walking behind her, lighting her path from the back. He caught up with her after two giant steps.

“You need to add value to the people Sambo, that’s the first step. Value addition starts with the people, that’s what The Great Farmer King would do, isn’t it?”

Zole’s home was now visible.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-11221945-1512168579-8058.jpeg.jpg)

On seeing it, she started humming a familiar tune. They trudged on, she hummed some more. Sambo tried to make sense of the of the song but could not. She saved him from the mental torture as she started voicing the lyrics:

Who can say where the road goes

Where the day flows, only time

They approached the door, and Zole continued humming the song. She loved, it she once told Sambo, because it tells one simple truth of life. That only time can really tell what will really happen: Whether The Great Farmer King will deliver on his 4 agendas or not.

Even as the door opened from the inside, she kept on singing:

Who can say if your love grows

As your heart chose

Only time

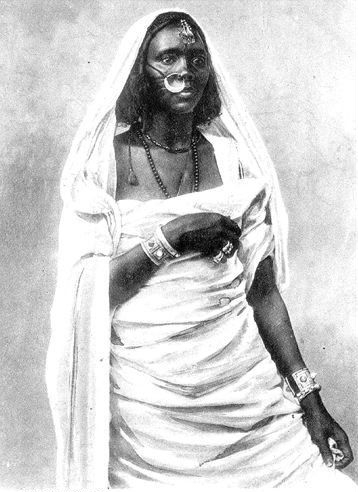

The opening door revealed her father, standing in front of it ready to welcome them. He was dressed in a white kanzu beneath a black coat. On his left hand, he held a brownish Misbaha. His henna-dyed beard shone a brilliant red as the light from Sambo’s torch touch it.

He switched it off and placed the phone back inside his pocket. Excitedly, Zole approached her father and embraced him warmly. Then, he stretched his hand towards Sambo and shook his hand firmly.

As the two men walked towards the living room, Zole stared out into the vast, dark slum that is Kibra. Finally, she started closing the door. Slowly, the light started receding as the darkness took over. Even after completely closing it, she, in her mellow voice, could still be heard singing her song:

Only time